In the foreword to La vie matérielle, published in 1987 (in English, Practicalities, 1990), Marguerite Duras points out that the personal stories, souvenirs, and thoughts she deposits are not fixed beliefs but fleeting and momentary pictures of herself. With this unclassifiable text, Duras avoids both the autobiographical genre and the spectacle of the intimate to leave traces of her daily and practical seventy-three-year experience as a writer and a woman. Even though the context and the nature of this fragmentary textual enterprise radically differ from the books that interest me today, when diving into them, I immediately thought of the poetic archive of La vie matérielle.

“Archive: Tamy Ben-Tor & Miki Carmi,” Minerva Projects, New York, 2021

(…) At most the book represents what I think sometimes, some days, about some things. So it does incidentally represent what I think. But I don’t drag the milestone of totalitarian, i.e., inflexible, thought around with me. That’s one plague I’ve managed to avoid.” Marguerite Duras, La vie matérielle (POL, 1987). “Practicalities,” trans. Barbara Bray (Grove Weidenfeld, 1990)

The artist book entitled Archive: Tamy Ben-Tor & Miki Carmi, recently published by the New-York-based Minerva Projects, constitutes a concrete reflection of over twenty years of performance, writing, video, photography, painting and drawing practices by the two artists Tamy Ben-Tor and Miki Carmi.1 Being the second collaborative book between the two Israeli born artists – who are also life partners – Archive maps their on-going collaboration since 2008, a few years after they met in New York, where they still live.2 Archive not only documents the artists’ works, but it traces their archiving looks on their art practices, in an intimate way but never through spectacle or reification of themselves.3

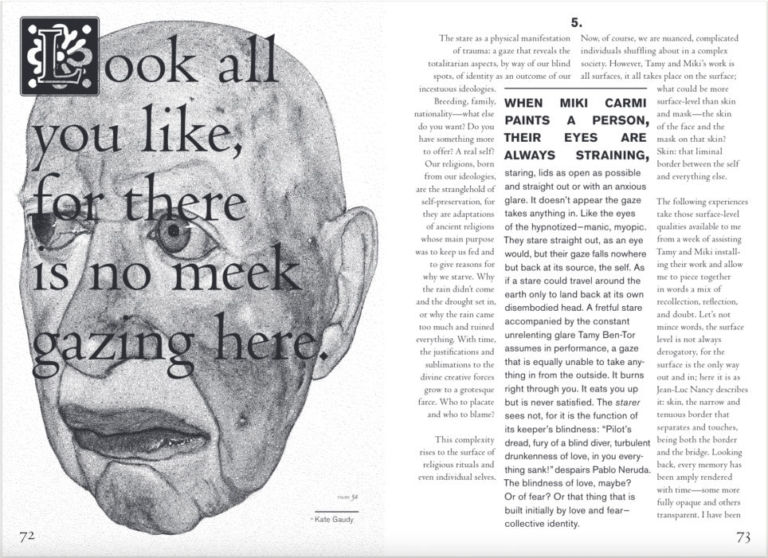

Archive is accompanied by a second book published a few months later by Minerva Projects, called Text Book: Tamy Ben-Tor & Miki Carmi.4 This ninety-page book gathers around ten commissioned texts written by six artists and scholars. Remarkably designed by Joshua Gamma, Text Book is an original collection of various voices and textual forms. It includes a text by Martin Brest, some poems and a short story by Norman Chernick-Zeitlin, experimental essays by Kosuke Kawahara and Kate Gaudy, theoretical texts by Alpesh Kantilal Patel and Coco Fusco, notes from a studio visit by Adara Mayers, as well as abstracts of Ben-Tor’s texts. Text Book attests of the endless marks on the viewers’ and readers’ consciousness the encounter with Ben-Tor and Carmi’s art provokes.

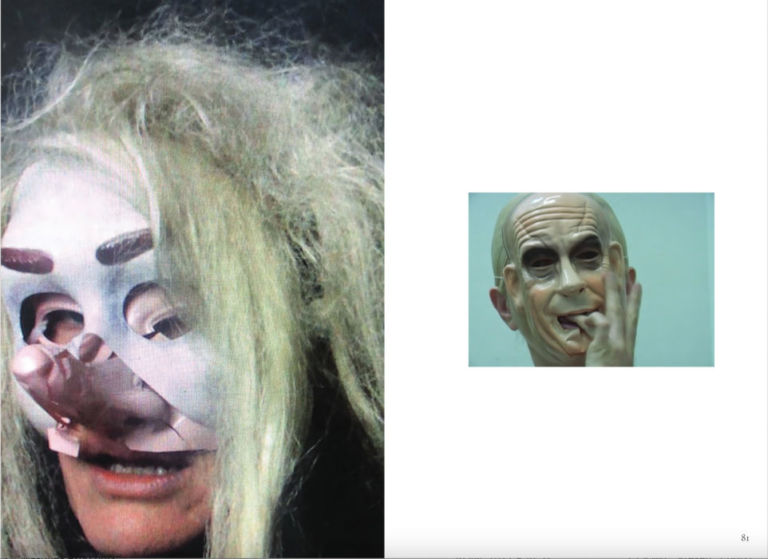

Made of various materials, these multiple-hand written books express at many levels the tensions between individuality and multiplicity. Double in its inner principle, as Archive and Text Book do not deal with one but two artists, this book-format diptyque is also multiple. In Archive, the reader encounters probably a hundred human faces. From Carmi’s family members that he photographed over the past twenty years and his well-known large painted human faces to the dozens of characters played by Ben-Tor in her performances and videos, as well as numerous figures of Carmi’s drawings and sketches. By a thoughtful composition of these heterogeneous materials, mediums and formats, these multiple faces dialogue in a tragic and grotesque Human Comedy.

Painting and documents: Carmi’s faces in front of history

How do these figures interact? On one double page, a green-blue-eye lengthened profiled figure painted by Carmi turns towards a series of two (and two other halves) photographs of Carmi’s grandparents which are printed vertically5 One may ask: is the painted figure the same old man from the photographs? Or does he know and sorrowfully remember the photographed couple? The questions remain unanswered.

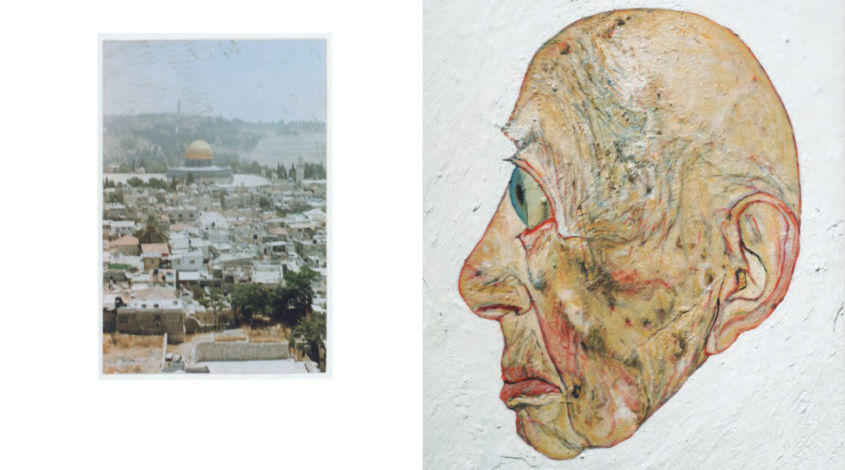

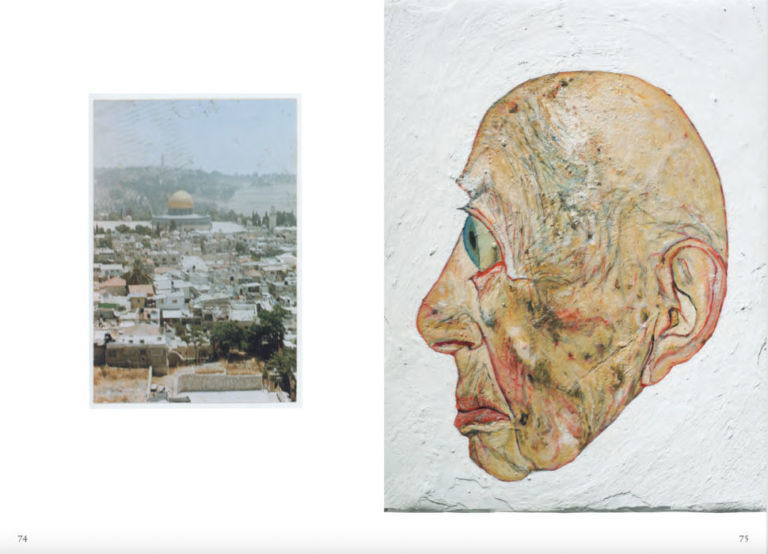

Twenty pages afterward, one of Carmi’s painted profiled face, more expressively textured than the others, turns towards a slightly blurred photograph of Jerusalem’s Old City rooftops.6 The white textured background of the painting and the stains on the figure itself mirror the overexposed concrete rooftops of the city. Suddenly, what is probably the effect of the Jerusalem blazing sun appears to me as piles of snow, the same snow which surrounds and lashes the old face from the right page.

The juxtaposition of these images, a face and a city facing each other on a surrealist scale – the face being bigger than the conflictual Jerusalem city – opens up multiple references and meanings, from the climatic determinist theories to the Zionist idea of belonging to the promised Land. Or maybe it is a way to evoke a possible analogy between the skin and the map?7 These many layers reflect the multidirectional memories that are encapsulated in Carmi’s practice, which he describes as “his lifetime project of mapping the physiognomies of [his] family traits”.8

“Archive: Tamy Ben-Tor & Miki Carmi,” Minerva Projects, New York, 2021

Through Text Book, multiple layers of these wrinkled faces are explicit. Coco Fusco, in her text “Eros and Tanatos”, claims that when repetitively painting his family relatives as “enlarged, shorn and detached from bodies” figures, Carmi “revisits political uses of portraiture produced as evidence of claims made by 19th and 20th-century scientists about correlations between ethnicity, physical traits, behavior and intellect.”9

For Alpesh Kantilal Patel, Carmi’s fleshy treatment of these faces allows “the possibility for subjectification rather than only objectification to take place.”10 This tension between subjectification and objectification by portraiture is densely expressed in the double page where a floating old face stands three quarters on to four mug shots of “Zwei Kurden” [Two Kurds] from Hans F.K. Günther’s Short Ethnology of the German People (1929).11

As many of these pseudo scientific experimentations have been theorized and massively diffused through books, Archive’s documentation of Carmi’s process is adding another layer to the painter’s reenactment, and conjuration, of the 19th-20th human objectification.

Maybe should I add that while observing Carmi’s painted faces, floating in space and time with their winding looks, I saw flickering the Angel of History that Walter Benjamin describes as following : “an angel who seems about to move away from something he stares at (…) His face is turned toward the past. Where a chain of events appears before us, he sees one single catastrophe. (…) This storm [from Paradise] drives him irresistibly into the future to which his back is turned while the pile of debris before him grows toward the sky. What we call progress is this storm.”12

“Archive: Tamy Ben-Tor & Miki Carmi,” Minerva Projects, New York, 2021

Resisting normality: archive of a struggle

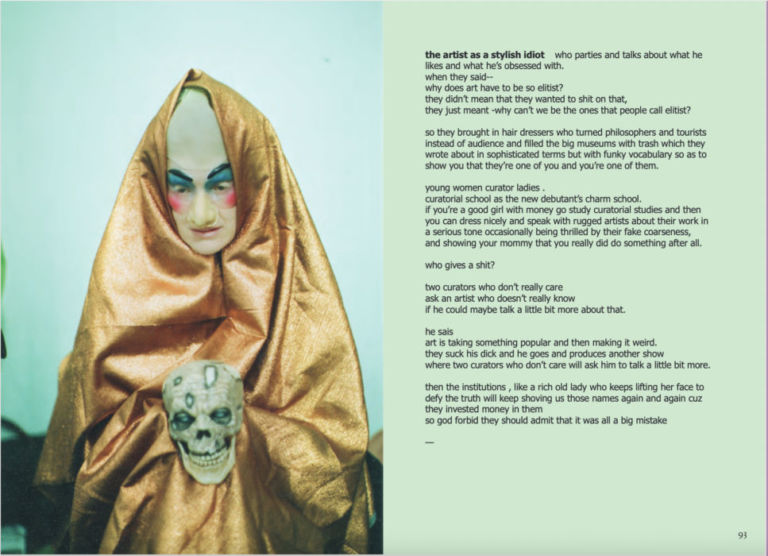

The tension between individuality and multiplicity, the figures of the self and the other is at the heart of Ben-Tor’s part of Archive book. The entertwinement of these perspectives and forces is conveyed through the dozens of images and texts documenting Ben-Tor’s continuous transmogrification.

In Archive, Ben-Tor appears in more than fifty radically distinct features: from the photographs of her live performances and her studio daily practice to stills of her videos (some of them are co-edited with Carmi). This flux of images – unidentified by specific titles or dates – thoroughly blurs the artist’ figure and body, echoeing what Martin Brest tells from the first time he attended Ben-Tor live performance in a gallery in New York: “Each woman I saw could have been her – there was no way to have sensed how tall or short, young or old this “performer” actually might be (…)”.13

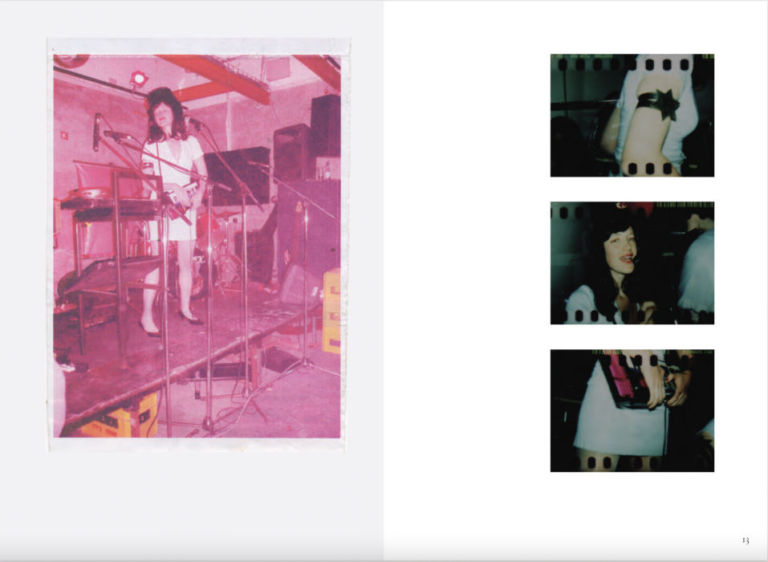

Moreover, as a compilation of twenty years of practice, Archive also allows the reader to concretely trace Ben-Tor’s perpetual metamorphosis in an unusual way. First of all, the precedently unseen photographs of Ben-Tor’s early performances in Jerusalem underground theater and Tel Aviv night clubs, which are included in the book, allows the reader to catch a glimpse in Ben-Tor’s original background.

“Archive: Tamy Ben-Tor & Miki Carmi,” Minerva Projects, New York, 2021

While wandering this montage of images and texts, the ones who already met Ben-Tor’s work will surely recognize some of her eccentric personae or the erratic speeches. Plus, reading Ben-Tor’s performed texts allows to precisely apprehend Ben-Tor’s writing skills. Especially the way she plays with spelling, punctuation and versification to textually – and visually – express accents and tones, and the political, social and cultural meanings they mark.

For example, in a text entitled “Spirit of Dolarat”, a curator with an ilegeable accent (somewhat of the world of Japanese Noh theatre) religiously recites what “an old wise collector” said on “that german painter” [Neo Rauch]. As an ultimate truth, she repeats:

“He say –

He da bes.

In da worl.”

When Ben-Tor plays with the spelling of this sentence, “he is the best in the world”, she both transcripts a racist idiocy of an exaggerated Japanese accent and mimics the arrogance of plebeians (aka collectors).14

In another text called “I wanna be considered open-minded,” a self-satisfied liberal, progressive, tolerant white woman claims her great merit for “tolerat[ing] you.” “Alert[ing] the police about you,” she says:

“Iiii feeeel sooooo

calm, relaxed and civilized”

The apparent spontaneity of the first verse is canceled by the juxtaposition of the three adjectives with the repetition of the coma. It reveals the intertwinement of neo-liberal ideology, racism and yoga meditative practices.15

Nuancing and texturing the language are ways to textually situate its uses and the political, social and cultural identities and situations they reflect.16 This is crucial as paradoxically, all over the book, the “I”, though printed in different fonts and sizes, is everywhere. This chorus of egocentric human voices reflects a wide spectrum of “the monstrous characteristics of human” (Kate Gaudy).17

“Archive: Tamy Ben-Tor & Miki Carmi,” Minerva Projects, New York, 2021

In the turmoil of this endemic “I”, the reader will certainly notice, here and there, short sentences – not necessarily using the “I.” These are Ben-Tor’s notes, which she defines in her minimalist introduction as “journal outbursts, unfinished manifestos, quotes and deflated screams.”18

Some are keys to understanding one of the common points of all her played characters: “Pumping up the volume on “Normal” exposes its perverse nature. It’s actually a hysterical repression of life.”19 Others are genuine reflections on her urge to embody the real as a daily practice: “A kind of demonic dance of illnesses (…) embodying the enemy as a cathartic victory. (2014)”20 Some others are fragments of what forms a strikingly lucid pamphlet against the superficial and aestheticizing treatment of political and social issues by elitist contemporary artists, curators and institutions.21

In these fragments, one perceives some of Ben-Tor’s crucial statements, such as her refusal to aestheticize the real. In her live performances, Ben-Tor turns the codes of theatrical illusion upside down, mainly by switching costumes in front of the audience. As Kate Gaudy highlights: “Though there is a mask, it is unmasked: extension cords and costumes lay strewn on the floor, the mechanisms of manipulation are not hidden.”22

Regarding her videos, their deliberate low-tech quality immediately avoids aestheticization too. In Archive, juxtaposing Ben-Tor’s performance and video texts, personal notes, fragments of manifestos, along with two quotations (of the Israeli iconoclastic writer and Holocaust survivor K-Tzetnik and the African-American comedian, writer, and civil rights leader Dick Gregory), is also a way to unmask Ben-Tor’s intention and process.

“Archive: Tamy Ben-Tor & Miki Carmi,” Minerva Projects, New York, 2021

As Martin Brest writes, “Tamy and Miki’s un-self-protecting work never, ever attempts to hide its asshole in the pursuit of revealing fundamental truth about the understanding of human experience with all its attendant pain.”23

In this equilibrium between art and life, Archive actually stands on a rare and narrow path. On the one hand, it does show how Ben-Tor and Carmi’s art practices develop and occur in the artists’ situated times, bodies and spaces; on the other hand, it never turns the artists’ intimacy, history, or daily life into an artistic material in itself.

Archive avoids the mise-en-scene of oneself, yet so present in our time. In fact, the imperative to show the process – a creative process and the process of making a book – lies at the heart of Archive.

A new grammar of reception: thinking in a labyrinth

As a mirror to Archive, Text Book’s chorus of various situated voices, perspectives and textual forms operates as an alternative grammar of reception, especially of writing on art. The various encounters between theory and fiction, dream and reality, experience and imagination, do not flatten and relativize them all but concretely allow the reader to trace the impacts of Carmi and Ben-Tor’s art on the writers’ consciousnesses.

In fact, within this labyrinthine network of writings, the reader – who might be disturbed at first – is soon contaminated by this new grammar of reception and experience. As Ben-Tor simply words it, “It’s a beautiful thing to show the audience, not – what I think, but the fact that I am able to think.”24 And this is what happens – the reader is triggered to think, imagine and self-reflect when wandering Carmi and Ben-Tor’s traces in these two books.

Opening Archive and Text Book is opening Pandora’s box, which shows tons of figures and voices. They look at us, they shout and cry, and sometimes lie. And in this grotesque crowd, like facing one of James Ensor’s carnivalesque scenes, each of us will see himself/herself, his/her family, friends, enemies and ghosts.

“Text Book: Tamy Ben-Tor & Miki Carmi,” Minerva Projects, New York, 2021

***

Archive: Tamy Ben-Tor & Miki Carmi, Minerva Projects, New York, 2021.

Text Book: Tamy Ben-Tor & Miki Carmi, Minerva Projects, New York, 2021.

Books Launching at CCA: Tel Aviv-Yafo, August 11th, 2022, 8pm.

***

Press bellow to show all comments