Collective Memories. Gray, cloudy skies are framed by geometric forms made of concrete: a cylinder connected to an oval by a rounded surface, another rectangle meets another rounded surface. There are markings in the rhythm of the concrete, textures, lines, change in tones. Perhaps it’s wet. Another image is occupied by concrete, flattening our point of view. Names of locations appear in Hebrew—Tze’elim, Hazerim, Halutza, Urim. Dotted lines have been carved, marking borders: a map embedded in stone. These close-ups offer partial views of Israel’s famous Monument to the Negev Brigade, designed by Dani Karavan. This site commemorates the fallen Palmach warriors who fought Arab forces in 1948, during the devastating war that followed Israel’s Declaration of Independence. Sprawling in the desert, the monument asks to underscore local history and continually recover it, eternalizing both a particular form of memory and itself as the embodiment of this memory. Although a caption tells us we are situated at the monument, it is unrecognizable in these images. At the same time, it seems eerily familiar. We remain trapped between the brutalist geometric shapes that define (or block) our view.

Black and White. A man is sitting outside, leaning against a brick wall. The wall is perpendicular to a fence, where we might have expected to see another brick wall, another side of a house. On the ground, framing him are rows of exposed bricks and a cable running above them. Seated at the center, the man has TV sets to his left and right, although the latter is emptied, leaving a shell of an appliance, which at some point probably brought the world much closer to its viewers. He is sitting on what seems to be another TV set. An open, half full bottle at his feet. He is holding a sock, getting ready to wear it on his right foot. We seem to be observing a scene that should have happened inside, but for some reason, the walls have been lifted, or forcefully removed, and we see the man in bright sunlight. The title simply reads Hebron, 1985.

Bearing Witness. As a child, Dana Arieli remembers her grandmother glued to the radio, seated by her small formica table in the kitchen in Jerusalem, across the street from the house where Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu grew up, listening to The Search Bureau for Missing Relatives, which, between 1945-2002 tried to help Holocaust survivors re-connect with relatives. She was waiting to hear any glimpse of information about family members, friends and lives lost without a trace during WWII. “I remember she was talking to a friend as they were listening to the broadcast, who told her how he was trapped in a chimney for two days with his cousin,” she tells me, “I remember how it took me years to understand their conversation. I remember what it means to go to the grocery store and all the adults around me have numbers tattooed on their hands.” In The Zionist Phantom project, she bears testimony to their traumas, while unfolding the complicated emergence of trauma in Israel’s public spaces, from monuments to the fallen in wars and terror bombings, to abandoned Arab villages, schools, museums and city streets.

Arieli’s photographic viewpoint accumulates unexpected moments in the landscape, amassing them as relics, as evident presence of what is now gone. For the past decade, she has been documenting abandoned and active spaces, unfinished buildings, military presence in civilian areas, sites of collective remembrance and personal loss. W.J.T. Mitchell observed that monuments desire “to live forever. They don’t want to die, they want to survive, they want to defeat death […] to defeat history [and] to be alive in the present […].”1 Arieli’s camera intensifies this battle to defeat death and history and “be alive in the present,” as it becomes a collecting device for what remains: “I am peeling off the layers of reality, realizing we grew up and continue to live within traumas, where one event chases the next and there is no moment of peace.”

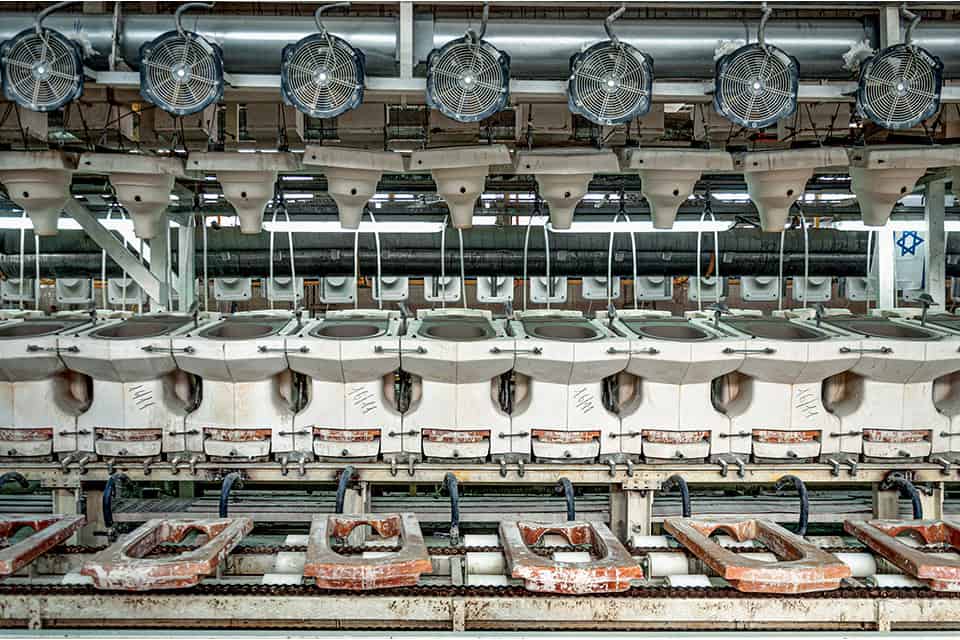

Hemet factory, 2012

The Israeli landscape is haunted by ghosts. Assembling what she refers to as “a worldview,” Arieli shapes a panoramic view of a landscape defined by the uneasy presence of its missing limbs. The idea of the phantom reflects what should have been there, and, beyond a sense of longing, it conveys a sensory experience: of what the mind wants to see or hear, what the mind is convinced—even momentarily—is, in fact, there. And yet, we tend to discover, the sound or sight is a misunderstanding, an internal malfunction. More than conveying what was there, the phantom experience exhumes what will never return.

In this iteration of the project, we also unearthed the ghosts of Arieli’s own practice: in each category before you, we traced her journeys to these sites and cities, including images captured as early as 1983, before she began identifying phantoms, tracing changes in place and time, but also in the artist’ own perception and visual interests. The streets of Jerusalem of the nineteen-eighties tell different stories than they do now. The people documented in “Labor Movement ” have changed since she began observing factories and small businesses. Trucks loaded with standard loaves of bread, dropping them off at local grocery stores, have been replaced by elaborate technologies. Small plants grew into factories, laboring minorities were replaced with other others. In recent years, Arieli had spent more time in and with buildings, silent ruins devoid of human presence, museums commemorating national narratives, or educational institutions that defined Israeli scholarship and innovativeness, but somehow seemed emptied, almost exhausted.

The Phantoms project actually developed at a distance from Israel. It emerged from Arieli’s prolonged scholarly research of dictatorships, starting with the Weimar Republic and its devastating fall. Political scientist, visual researcher and an artist, she began capturing what she saw as relics of dictatorships in public spaces across Europe, beginning with Germany. It was in buildings, open landscapes and sites of commemoration that she noticed the remnants of the past that continue to shape memory and its perception, as their ghostly presence is embedded in the minutia of the everyday, in streets, buildings, abandoned estates. For Arieli, the photographic image can create new understandings and trigger collective and personal processes. Sometimes, she writes, the image can generate substantial social change.2 And so, what was planned as a single journey to Germany more than a decade ago, turned into thirty-five excursions to Europe, and over one-hundred journeys across Israel.

IDF collection, Tel Aviv, 2017

is/was. The capturing of the landscape belongs to a more complicated, perhaps intimate, system of decoding, categorizing, cataloguing and archiving, within which Arieli’s camera operates. The Zionist Phantom is also a complex archival system, which currently travels the world in digital form (website) and printed postcards, which can be reprinted, distributed and commented upon. At her home in Jerusalem, Arieli receives written responses and comments from people worldwide, which are added to the project and its growing archive of new writing of the landscape, both visual and textual.

Artist Lorrain O’Grady sought to view a world beyond hierarchical binaries of either/or, both/and. She created diptychs that brought both poles of binaries together, seeking to change their epistemological dynamic. When aligned, one can never take precedent over the other.3 Arieli’s phantoms, in digital and printed forms, offer a way out of binaries of western and, specifically, Israeli culture, as they observe the landscape through what is and what was. Repositioning the binaries of either/or, of one triumphant narrative, one prevailing trauma in the landscape, the missing limbs emerge not as contradictory terms, but as an endless conversation.

Warning signs. I ask why did she turn her camera toward Israel, in the framework of a project that began with fallen totalitarian regimes. The roots of that shift are embedded in her research of another trauma, a watershed moment for Israeli society. On November 4, 1995, Yigal Amir assassinated Yizhak Rabin, the Prime Minister, in an attempt to sever Rabin’s attempts to adopt the radical possibility of regional peace. “The first sign in the rise of a dictatorship is a political assassination, all the more so when a presiding Prime Minister is murdered,” Arieli notes, “That’s the game changer, the most extreme sign of ex-parliametary activity – our point of no-return. It undermined everything that had characterized Israeli society up to that point. As a researcher, I had to examine that moment, I had to shift from dictatorships to a democracy at a volatile juncture.” She organized exhibitions about artistic responses to the murder, and her 2005 book Creators in Overburden: Rabin Assassination Art and Politics won The Prime Minister’s Prize. She continued writing about the murder, and later, when the phantoms emerged in her research, they led her to re-think Israeli landscapes as well. “Dictatorships,” she adds, “continue to live in the shadows of democracies established following WWII.”

Missing limbs. “Only when I began to write about phantoms was I able to process the traumas that have defined my roots,” says Arieli, “The first time I visited Poland, which is such a complicated place for me to visit, it smelled like home. It was the first time I understood my grandmother’s home.” As noted, the phantoms she gathers of Zionism, as an ideology that is present as much as it continues to change and redefine itself, travel as sets of postcards in three languages—Hebrew, English and Arabic—asking viewers and participants in workshops and events to contribute their impressions of the images. These reflect unexpected memories, experiences and associations that reposition the photographic images, and charge the documented sites with additional meanings. This mobile gallery continues to develop and offer new possibilities for endless conversations, seeking to transform personal pains and heartaches to spaces for dialogues and global engagements.

This article was first published on Schusterman Center for Israel Studies website. The text was published in conjunction with Prof. Dana Arieli’s virtual exhibition The Zionist Phantom, organized by the Schusterman Center for Israel Studies at Brandeis University, curated by Dr. Rotem Rozental.