Vienna at the turn of the twentieth century, capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was a city of contradictions. It was the home of psychoanalysis and of modernist architecture, but also of rising waves of socialism, anti-Semitism and moral crisis. Many Jewish thinkers and artists took part in this unique period of awakening of new disciplines in science and art. Jewish artists benefitted from this unique environment by acquiring the necessary knowledge and experience from advanced institutions and private artists alike. Over the years several of them remained in Vienna, while others, especially after World War I, immigrated to Palestine, participated in the development of the pre-state’s cultural life, and left a deep imprint on Israeli Art.

One of the most comprehensive Israeli private art collections today that holds works in various media by Jewish and Israeli artists with a strong Viennese connection is the Levin Collection, assembled over a period of forty years by preeminent art historian and curator of the art and culture of Israel, Gideon Ofrat. The collection was purchased more than ten years ago by Ofer Levin, a financial strategist and art collector, and ever since has continued to mature, develop, and expand.

“Jewish artists from Austria,” explains Ofer Levin, “both those who remained in Europe and others who decided to eventually immigrate to Israel constitute an important part of our collection. Along renowned artists such as Anna Ticho, Leopold Krakauer or Ludwig Bloom one could also find artists who were unjustifiably forgotten in the context of Israeli art, for example Kraukauer’s wife, Grete Wolf, Osias Hofstatter or Jane Schacherl-Hillman.”

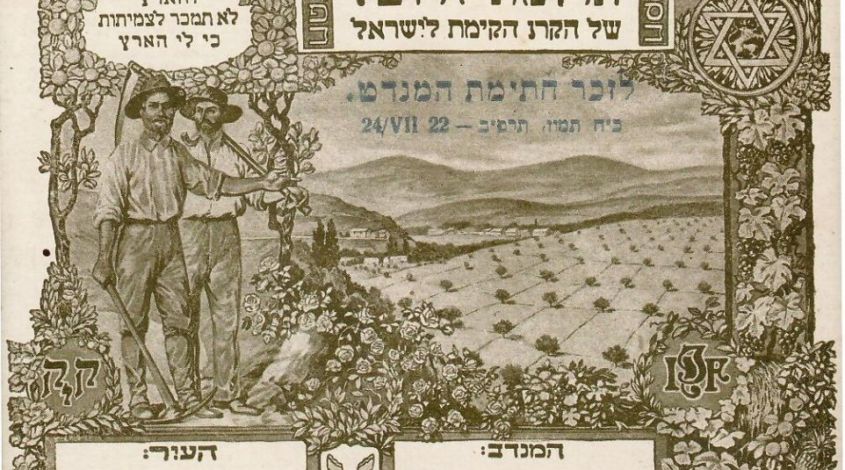

The earliest representative of this “Austrian” group of artists in the Levin Collection is Emil Ranzenhofer, who was born in Vienna in 1864. He began studying at the Vienna Academy of Applied Arts in 1888. Ranzenhofer worked in the service of the Zionist Movement at the beginning of the 20th century. According to Gideon Ofrat, he adopted E.M. Lilien’s Jugendstil language and modeled Hebrew pioneers who appeared like typical Austro-German farmers, framed with floral ornaments, the seven species of the Land of Israel, a Star of David, etc. In 1903 Ranzenhofer designed the official postcard of the Sixth Zionist Congress: a Hebrew pioneer standing amid rocks in the field holding a spade, as a mythological winged beauty, engulfed by sheaves and holding up a palm branch, rises opposite him. “Ranzenhofer’s style”, points out Ofrat “reflected the turn-of-the-century style, as often manifested between Paris and Vienna in those years.”

But it was the Jewish artists who did choose to immigrate to Palestine that contributed the most to Israeli art. Anna Ticho, born in Brno in 1894, also received her art education in Vienna at an early age, left Austria in 1912 and settled in Jerusalem. On that same year she married Avraham Albert Ticho, an ophthalmologist. For 30 years she assisted her husband in his clinic in Jerusalem, which received countless patients – Jews, Christians, and Muslims, but never abandoned her art. She became renowned above all for her drawings of the Judean Mountains, the alleyways of Jerusalem and the city’s olive trees.

“The drawing by Anna Ticho,” emphasizes Ofrat “is distinguished by the juxtaposition of realistic fidelity to the landscape and the liberation of the hand in spontaneous-lyrical motion devoid of any representative quality, and which shifts from the objective world to the artist’s subjective world.” It was in the 1960s, when some drawings of hills and villages created by Ticho in Jerusalem and its surroundings began acquiring an independent status; it originated indeed in the shapes of the wadis, terraces, shrubs, rocks, etc., yet culminated in transfiguration – the artist’s near-total liberation from visual dependence on the realistic landscape and its re-creation in her home-studio as an independent visual piece. Indeed, some of Ticho’s landscapes from the 1960s’ come close to abstract-action drawing.

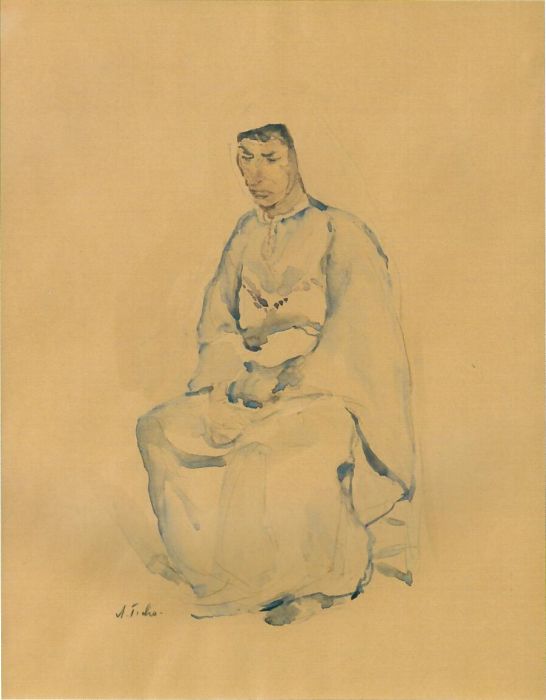

Another recurring theme of her drawings was the numerous figures she drew in Jerusalem of beggars, female nudes, and more, a human complement of the landscapes of ruins and the arid Judean mountains in which she specialized. Arab for the most part, these figures were painted from the late 1920s to the late 1950s, introducing the beggar as a human ruin with a somewhat mysterious aura.

Anna Ticho, Seated Arab Woman, 1940s(?) | The Levin Collection

Ludwig Blum, another Moravian who was born in 1891 set off to Vienna in 1910 to study painting. He began his studies at the private school of David Cohn, a Jewish orthodox painter of Hungarian heritage, famous for his portraits of Viennese nobility, and known in the Austrian capital as the “Kaiser family painter”. Blum will remain with Cohn even after he began studying at the Vienna Art Academy while keeping his distance from members of the Viennese Secession. He later left Vienna for Prague and studied under the Austrian Professor Franz Thiele, master of landscapes. After completing his advanced studies at the Prague Academy, Blum traveled between Europe’s leading artistic centers, and finally arrived in Palestine in 1923. However, he made no contact whatsoever with the Bezalel art school.

“As a painter of the temporal,” comments Ofrat about Blum’s style, “he was a historical-Zionist painter. However, he did not paint huge canvases extoling grand victories and heroic apotheoses, but focused on their particular, intimate and human manifestations. In contrast, as a painter of the ‘timeless’ Blum shifted his gaze from the close and immediate to the far and elusive, to the sublime. He showed preference to the panoramic and the ‘boundless in nature.”

One of Blum’s best-known ‘timeless’ paintings is from his series of Jerusalem panoramas, yet another proof attesting to the academic virtuosity of this artist whose brush skillfully “photographed”, as coined by Ofrat, the country’s sacred sites and tourist attractions. In the painting an Arab shepherd is seated with his back to us, in the midst of billy goats, observing from a distant slope which seems the lower parts of Mt. Scopus, toward the Old City and the surrounding hills. The Orientalist landscape perception is familiar, yet Blum’s ability to capture the hues and nuances of light, and the gradual fusion of land and sky at the horizon is quite impressive. There was no picturesque spot in Jerusalem that was not depicted by Blum.

Ludwig Blum, Jerusalem, 1943 | The Levin Collection

“During his life,” continues Ofrat “not one painting by Blum was exhibited in a central Israeli museum, despite his popularity among publics in the country and abroad, not to mention his artistic gift. The reason Blum’s art was excluded cannot be disconnected from the passion for the modern in whose grip the local world was held since the 1920s.”

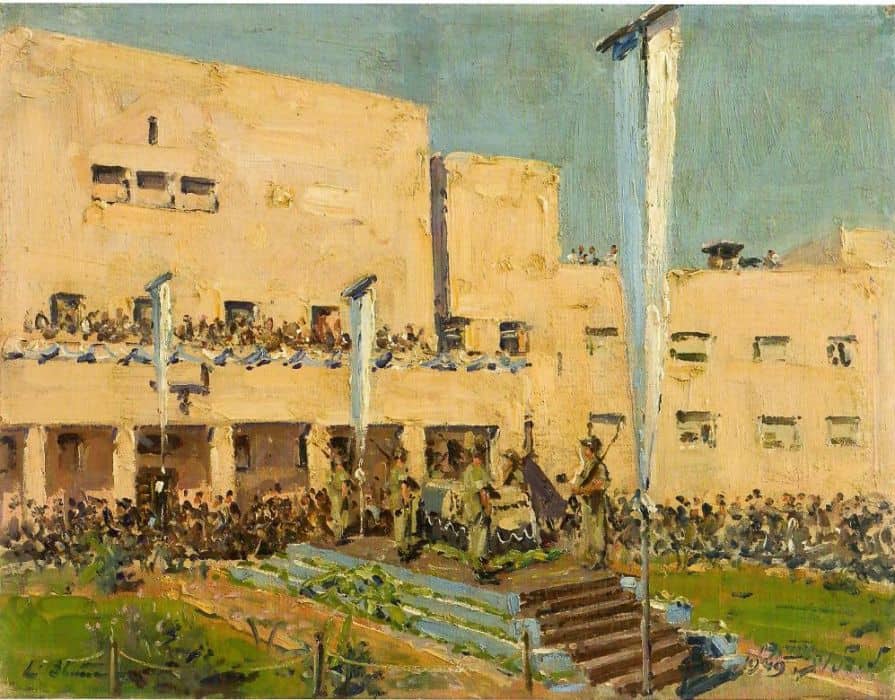

“Ludwig Blum is indeed a unique artist,” adds Ofer Levin, “Austria had been in this respect an artistic greenhouse for talented Jewish painters and sculptures. They later found their own artistic voice in a land whose roots can be found in the Bible, but at the time of their arrival, a new State was being formed. That is why to me, it is a great privilege to have in the Levin Collection Blum’s War of Independence paintings and drawings”.

Ludwig Blum, Herzl’s Funeral Rite by The Jewish National Institutions House

Jerusalem, 1949 | The Levin Collection

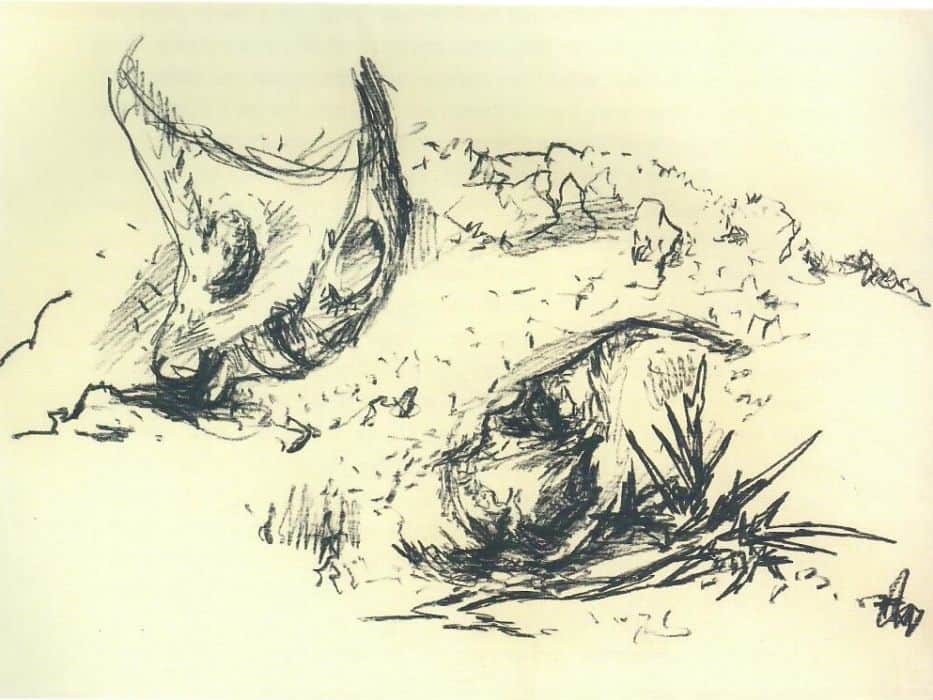

Bit by bit, Jerusalem became a small artistic hub especially with the arrival in 1926 from Austria of the architect and artist Leopold Krakauer and his wife Grete Wolf. Leopold brought with him from Vienna an Expressionist penchant, indebted to Oskar Kokoschka but also a sensitivity to Jewish mysticism. “Krakauer’s earlier drawings,” asserts Ofrat, “surrendered an apocalyptic air, manifested, for example, in his early drawings of Jerusalem. A dramatic nocturne engulfs these dim drawings. Within a few months Krakauer would begin drawing the Crucified Jesus and Jesus as a tree trunk in charcoal, writing a new chapter in the book of visionary, tragic Jerusalem.”

Leopold Krakauer, Head and Mask in the Judean Mountains, 1946 | The Levin Collection

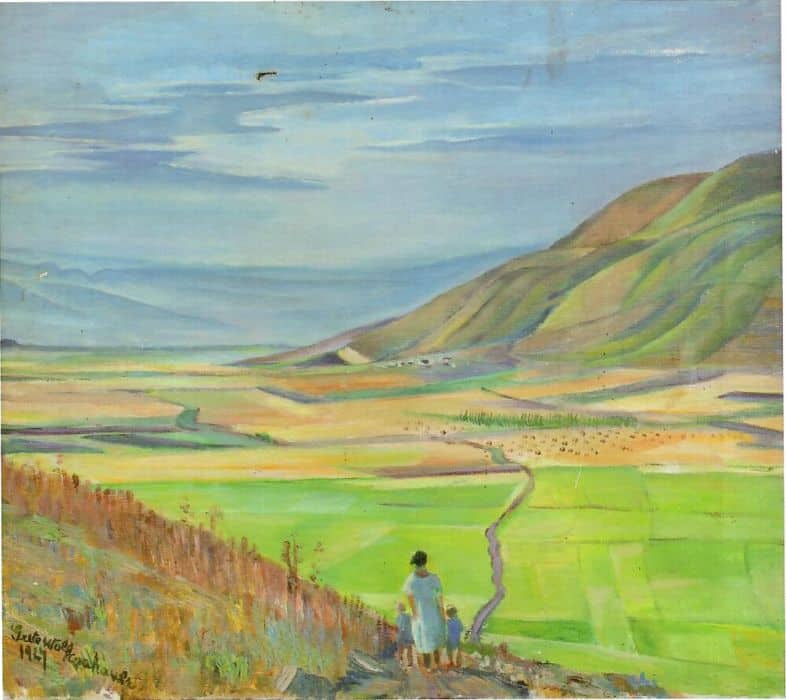

Krakauer’s wife, Grete Wolf, on the other hand, who also studied painting in Vienna and even gained recognition there as a portraitist, inclined early in her career toward Expressionism. Alongside graphic work, she painted portraits of local personalities, Jewish, Muslim, and Christian (including officials of the British Mandate) in figurative style blended with soft Cubism. The artist continued to create and exhibit in diverse venues. In 1931, during a year long sojourn in Europe, she presented a one-person show in the esteemed Viennese Galerie Würthle. During the 1930s, her painting was inclined toward realism. Henceforth Wolf Krakauer was gradually forgotten outside the consciousness of the “Erez-Israeli” art world, and the memory of her work faded in the shadow of her husband’s drawings and architectural work. The painting below portrays a mother and daughter standing on the peak of Mt. Gilboa, observing the panorama of the Jezreel Valley. “Motherhood is interwoven in this painting,” explains Ofrat, “with the experience of the country as a procreative motherland and the fertility of the Jezreel Valley, spread out in all its glory to reaffirm its Zionist-pioneering reputation.”

Grete Wolf Krakauer, Jezreel Valley, 1927 | The Levin Collection

Between 1933 and 1935 around 22,000 Jews immigrated from Germany to Palestine. By the year of 1939, the number of Jews arriving to Erez-Israel rose to 40,000. “Many Jewish immigrants from Germany channeled their professional experience and capital into commerce and the limited industrial sector, making wise investments,” says Ofer Levin, “in what was then a land of opportunities.” On the other hand, Jewish artists, many of whom completed their studies at German higher education institutions, became just a short time afterwards a substantial segment of the artistic milieu. A new wind was beginning to blow in Israeli art.