In light of COVID-19 outbreak and increased cases in New York City, on March 7th, Columbia University Students (myself included), Faculty and Staff were informed via email that there will be no in-person classes. During the following week, new measures and restrictions were being announced daily. On March 17th, a full shutdown of all non-essential research facilities, including the studio building was applied. On March 20th, A statewide stay-at-home order was placed and had yet to be lifted.

On March 17th, Dana DeGiulio, my professor and mentor, uploaded a short clip to her Instagram account. With “The Death of Marat” as its backdrop, a clumsy white clay figure started speaking softly towards me “Testing.. Testing.. Hi, I’m Dana DeGiulio, I am your professor, in these challenging times I want you all to know… egh..” Dr. Zoom was born. Twenty episodes in total, that ended along with the academic year. (Access all 20 episodes in 3 installments here, here and here)

I met with Dana for a Zoom conversation on 15 June, 2020.

Roni Aviv: How did it all begin, what were the settings that started off Dr. Zoom?

Dana DeGiulio: It’s funny to describe because we were all in it. I think that everybody just panicked and hustled and understood that they had to retain some sort of semblance of stability. Something about my role from March 12 had to be true on March 17. And I wasn’t sure what that was. Somehow I still had to be a professor at something. And I thought that that was kind of garbage.

I think that part of being a professor is performing some kind of stability, if not authority, and I wanted to admit to being as destabilized as the structures that typically hold us in place, and using soft, malleable materials seemed like the way to do that.

I didn’t know that Dr. Zoom was gonna happen. I was in my house, panicking, aware that I had 16 grad students to advise, sitting at my desk and trying to find something to squeeze. So it was like, Alright, is there a way to make a real time narrative about this?

I could still figure on the ground that was shifting really rapidly underneath everybody.

and since that was moving and shifting, I’m going to have to move and shift to, because art is not apart from the world for me.

Yeah, you’re in it. Dr. Zoom’s episodes have many references to art history, film, pop culture: you are setting up the stage, using certain tropes, to then break the stability of these structures over and over again.

Breaking it, or just pointing at its instability. I’m just poking my fingers in things where there are already holes. If anything, I’m getting my finger in there and making the hole a little bit bigger. Everything is softer than it looks, even and maybe especially ideology.

How’s that?

In the language around the institution and these types of resistance or rebellion, the sort of way that’s staged in the university and in art in ordinary time. It’s such a fucking musical. There were a lot of pronouncements right away: “this is what education is! this is what art is!” we must storm the fucking barricades or something. All of this is singing about things. And as far as tropes and clichés, they circulate really easily. It’s a particular kind of sensual manipulation, people get aroused by it. Some of the music is from the soap opera All My Children. I wanted things to be a little familiar, but not be able to mean in the same way.

Deflating its meaning.

Yes, taking the air out a little bit.

There is a moment where Dr. Zoom shouts “pedagogy”, marking it as a current buzzword. So what does it actually mean?

There’s lots of ways to answer that. One is etymologically, which seems like a cheap trick, but the pedagogue in ancient Greece was someone whose job was to take a child for a walk to and from school. They weren’t the teacher, they were the walker. The worker that walked with the student to the master. I am not interested in authority or in mastery. I’m interested in walking. Absolutely. In order to walk with somebody you have to know how they walk. They have to know how you walk. You figure out how you are together. I take that definition really, really, really seriously. My job is to walk with you. It’s an honor. That part is absolutely, to be with people at different stages of their journey, it’s a lovely thing. I’m genuinely grateful for it. I’m not grateful for these large neoliberal institutions that monetize and weaponized and corporatize that relationship.

I’ve heard the words ‘pedagogy’ and ‘community’, in a lot of zoom meetings. Suddenly, as talking heads, the department was very excited about Community. The limits are clear, authority is clear. I don’t have to think about somebody using their phone or tapping their foot when I’m talking. I don’t have to care at all. All I can do is to have this weird relationship to being a teacher somehow deposit information or care, as though it was a body of knowledge transactable and commodifiable that way. That’s what pedagogy became to me. The school is using language like “the student experience” for instance. I’m not a fucking tour guide, I’m not an affect vending machine or a trained clinician. It’s my position to wear the process out, to not take any of these perverted or bastardized words for granted. I don’t want it to be a part of your tuition. But I do believe in genealogy: My teachers are your teachers. We’re all part of this Frankenstein of all these people who taught us and outraged us.

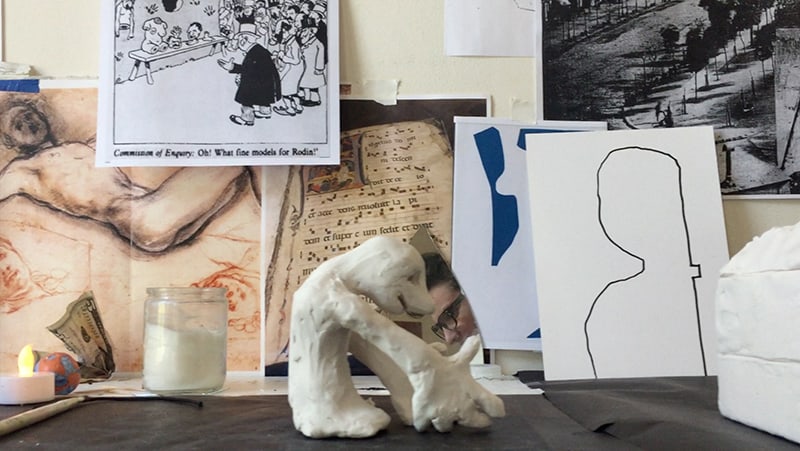

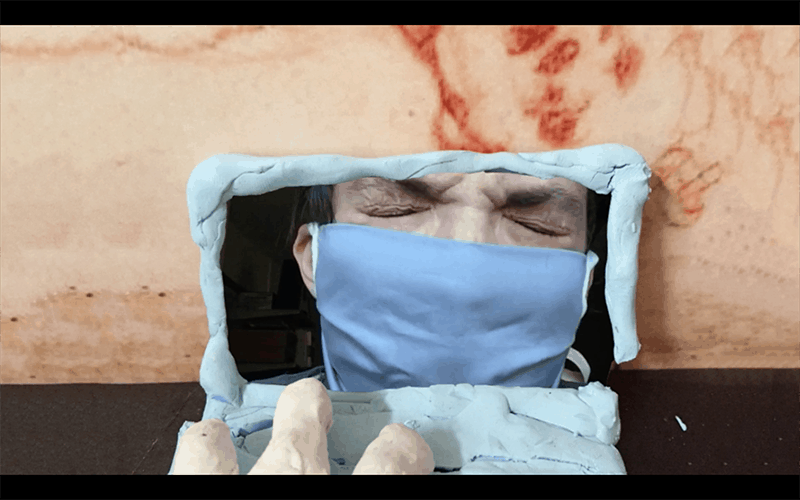

Dana DeGiulio, Stills from “Dr. Zoom”, 2020

I’ve noticed the episodes have fake endings. The viewer is left with an ambiguous line and a wink. You are using the format to show us how it’s not actually working out.

I like your point about the fake ending, that’s a painting thing. You don’t ever finish a painting, you just have to withdraw. When does it end? It ends at 59 seconds. Not by narrative constraint, or narrative resolution. You can feel it almost ending, and the music’s telling you it’s ending, and then it just stops.

As a walker, there is an amount of equality that you move towards, by adjusting your steps, that puts you in a vulnerable position. But Dr. Zoom protects you, so you can say anything, as its not you.

I recently spoke to a Columbia student on the phone, he said he was picturing Dr. Zoom talking. That’s ideal. This malleable, agile little clay figure is way more adaptable and honest than I could be. Inventing this little toy to say the things that I really mean. I can sync this little squeezy thing to my own voice, and it will hold my voice better. The institution gave me a rubber mask of my own face. That’s what it is, and I like the idea that a toy is better at being there than I am.

Better at being watched maybe?

Yeah, for sure. I guess part of its origins was that I was responding to a lot of artists around my age, that were making very impassioned addresses to the camera

“We as artists must do this!” You don’t know, we don’t know, admit that something is very wrong. I didn’t want to make some perverse cooking show of my own face.

Zoom felt way way more intimate then safe for me. You know, here we are staring into each other’s faces for hours. It’s like, what are we going to do in real life? Are you tall? I forget. What’s gonna happen? I mean, this is not the kind of intimacy I signed up for. It was like, here’s my house. That’s the sound of the person I live with. I don’t know where my bra is.

Yeah, all these preliminary conditions in which we operated, where Dr. Zoom started to operate were given.

I mean, I’m not a paramedic. But I want my work to be responsive to conditions as I find them. I woke up every day and I was upset every day. And there were more things to say, and after a while I felt like I had figured out how to make a little world that I was responsible for.

And as things progressed Dr. Zoom got deeper into a rabbit-hole of his own thoughts. You don’t even know that he is a doctor anymore. He is just a little person being lost, collapsing into himself, and staring in the mirror.

I felt like people were doing a lot of looking in the mirror. I know I was, you know, just to prove that I’m here I’m gonna take ten pictures of my own face, and just look at them. And making another little face to attend to have that address. I engage in clichés on purpose, flowers or car crashes, or wearing a little ghost costume. My whole thing is the breakdown of these kinds of signs and the material fungibility they possess. That’s all. When I trust the form that I’m using, I can totally fall apart inside of it, because it’s stronger than me. If the form or the trope or the cliché is durable enough, I can completely collapse or evaporate inside of it. Or space out or get bored or jerk off or disappear in the container. When Dr. Zoom became a tough enough container, I could really let it get soft, I could get soft inside of its shell. I wanted to show it happen.

Dana DeGiulio, Stills from “Dr. Zoom”, 2020

And it lingers there for a while.

Yes, stay with my work long enough and it gets real sad.

Can you choose a certain moment from the videos to talk about?

Well, I like the line “all my heroes are idiots.” I don’t know if this is a grand thing to say but I don’t believe in empathy. I think it’s arrogant to think that I could feel what you feel. I think that sympathy is essential and important for me to understand that I’m not you, and to understand and respect your feelings. I can identify them, but not graft my life onto yours in this way.

There are people in beds in Central Park, and I don’t know anybody who died from this. I am very lucky. I can’t imagine, I can’t get there. I can’t empathize. And in that episode, Jane Fonda is going to Hanoi during the war and attempting to empathize and use her power to side with the opposition. Which is an idiotic and very passionate and ardent and open hearted thing to do. St. Francis is getting Jesus’ wounds by the force of his imagination. These aren’t your wounds, you know, they’re not. They belong to other people who are genuinely suffering, who are your fucking neighbors.

Dana DeGiulio, Still from “Dr. Zoom”, 2020

I mean, this is not far away from the experience of state-sanctioned police violence on the bodies of people of color. I am complicit in this. I am in it. I am next to it. I am absolutely adjacent and a participant in it as a citizen of the species.

I think attention is extremely forceful. And that like, you can tend to things by killing them, you can tend to things by watering them too and let them grow. But I think that that’s where the sympathy part is important. It’s like actually acknowledging what it is you’re looking at, and who’s doing the looking. There’s nothing neutral about seeing something or being a person in the world, you’re always in a position. In order to care, and to worry, or help or actually attend to things, I have to admit where I am, what’s my limits and my edges.

I think that using relatively simple language, and words that I think that we know, whoever we are is important. When academic speech enters into my own speech, it’s always ironically, because I think it’s used as a weapon or as a capital intimidation. What is a teacher? There’s no reason to hide with more complicated language systems than the one that you know. In fact, I’m only clay. I only have little clay words. We all only have little clay words. There’s some filigree. Some ornaments you could throw on top of that to decorate that cake all day, but if it’s pound cake, it’s pound cake.

I hate pound cake.

I haven’t had pound cake in years.

And Dr. Zoom, by living on Instagram, he is not really your possession, right?

Oh, yeah, yeah, once it leaves my hands it’s not me for sure anymore. It can go without me. The text of Dr. Zoom is the text of Dr. Zoom as its maker.

It’s this pedagogical creature and what happens to it in a time of crisis. How it reveals its own wounds.

It makes me think of the car piece (Suburban, 2013), you are showing a structure, making cracks, exposing the places in which its porous to its surroundings. and the exchange is always about that touch of things.

Some days it didn’t work, I didn’t know what I was saying. Some days were just moosh. When Dr. Zoom slowed down, I realized that I actually was doing something. And it wasn’t just about having done it. I always want to be either the same size or a little bit smaller than my work. And when I got smaller than Dr. Zoom, I was like, Okay, slow down. You’re not just fucking around with clay.

And about the car, I want to say, I don’t know if it’s clear: the narrative was also a pedagogical move. That was my advisor in grad school who operated that space.

Dana DeGiulio, “Suburban”, 2013

Walk me through this work.

So I did it in 2013. Michelle Grabner, who co-founded and co-operated a gallery space in her backyard, asked me if I wanted to have a painting show. And I said, No. I want to drive a car into the building. And she said, yes.

It was one of the greatest moments of me being a student in my life. I wasn’t her student anymore. We’ve been done with our grad school relationship for six years. In Chicago when this took place in context, I was always like her fucked up goth gay teenager. A squirmy, arrogant, sad little rebel. And she’s a very serious, straight performative bourgeois. The mom, the authority who ran this small but powerful space that meant a lot to a lot of people. In order to buy the Car, I sold a painting she’d given me as a gift painting to her commercial gallery in New York, and bought the car. Economically, I was bringing her painting home. This piece is the most tender, precise and impersonal thing I’ve ever done. It was still a painting show. It was still a particular touch, a particular gesture. I had to prepare for it. I had to do math. I had to figure out how quickly I could go backwards and hit a cinderblock building so steel roofing wouldn’t fall on me. You know, like being beheaded would’ve fucked up my whole plan. I hit the building at 18 miles per hour, and by the way that it landed when the building started to fall on the bumper of the car, which ended up holding it up, which was maybe the best thing that’s ever happened to me. That’s completely what I meant. The car stayed there for the first month of the exhibition, just living in the yard. Someone put a note on it that said, ‘You suck at parking’. I like that kind of joke to be there too.

When I sold the painting, I budgeted into the purchase of the car enough money to rebuild the gallery. She didn’t want it. She was like “thanks for getting rid of it”. On the day that I did it, she cried, her husband cried, I cried. I was also super happy because I didn’t die. And it looked great. It felt like something that needed to be done, that I knew that I could do.

It also gave the space a very theatrical ending.

Yes, and she wanted people to see it again; this gallery space was there for ten years and people were just hanging out in the yard, drinking and not looking at the art. So it kind of disappeared. Suddenly, people were defending it. Someone wrote about the show and called me a “narcissistic terrorist” which, okay. But also, I wanted people to see this public gesture with the flower paintings, with everything else.

A lot of my undergrad students absolutely freaked out. They were like, “we’re afraid of you”, like, well, being an artist is a role. You don’t ask if the actor’s happy.

And the behind the scenes was visible to the audience.

I made a little pamphlet to show how it all happened. This is where the money went, this is the equation I tried to do to figure this out. Just so you know it’s not magic. it’s material and economics as ever.

And it’s wild because Michelle still has to talk about it. Years later, we have been on panels together and people ask “how could you sit next to her?” Like, fucking still? Like, come on people art is a real thing. And this thing is still fascinating to some, especially in Chicago.

I left town five months after, that was the selfish part of that I didn’t know how to leave – so I’ll just break it.

That was your old wink?

Yeah, I mean, that’s why the backwards, so I can drive out.