Often, in the art world, memory– especially relating to the Holocaust – takes strange and varied directions. Much has been written about it, both in the Israeli context (on artists such as Boaz Arad, Ram Katzir, Roee Rosen, and Gil Yefman), and in a wider context (on artists such as Zbigniew Libera, Piotr Uklansky, Tom Sachs, and Elke Krystufek). In 2002, a broadly inclusive exhibition dedicated to Nazi images in contemporary art – Mirroring Evil: Nazi Imagery/Recent Art – was held at the Jewish Museum in New York (curator: Norman Kleeblatt).

The art of Amsterdam-based artist Maarten van der Heijden (b. 1947) focuses on this theme. Van der Heijden was born in Amsterdam and studied from 2005 to 2010 at the Gerrit Rietveld Art Academy. His work is currently exhibited in the exhibition Jerusalem: Between Heaven and Earth (curator: Prof. Ori Soltes) as part of the exhibition The Jewish Art Salon at the Third Jerusalem Biennale for Contemporary Jewish Art. The exhibition is being shown at the Museum of Underground Prisoners, which is owned and run by the Israeli Ministry of Defense. The director of the museum, Mr. Yoram Tamir, demanded to see all the works that would be going into the exhibitions installed there. As Soltes, the curator puts it: “The director of the museum, without explanation or apology, simply said that five works were not acceptable.” Van der Heijden’s works are among the censored works, and instead of being exhibited at the museum, they are now being shown at the Bezeq Building, another venue of the Jerusalem Biennale (12 Chopin Street, Jerusalem).

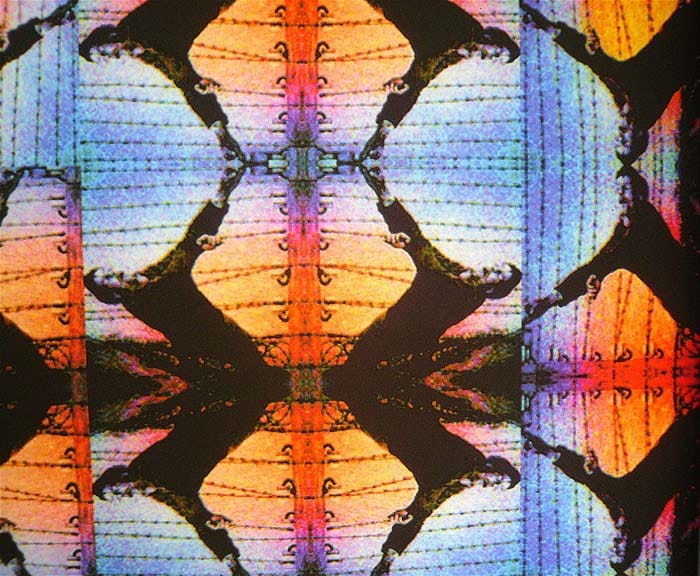

Van der Heijden’s works are created by digital means. At first glance, they are uplifting, beautiful, and pleasant. His series Grotesques (2010) with its bright colors, calls to mind Buddhist mandalas filled with repetitive forms and images. A closer look, though, reveals that the forms consist of complex and appalling images of naked bodies, all from photographs taken by American soldiers who liberated the concentration camps at the end of World War II. In the Israeli context, the beauty that disguises the atrocity is reminiscent of Zoya Cherkassky’s golden jewel-like Star of David (‘JUDE’, 2001-2002), which resembles the yellow-colored badge used by the Nazis during the Holocaust to identify Jews.

Maarten van der Heijden, Grotesques 4, 2010, framed C-print

The piles of corpses that fill the works of Van der Heijden also recall the provocative work Hell by brothers Dinos and Jake Chapman, which was exhibited in the exhibition Apocalypse at the Royal Academy in London in 2000. The Chapman brothers substituted piles of Nazi bodies for the piles of bodies associated with the murdered victims of the Shoah. Some may see in such works a type of a memorial and a monument to the victims, or a new, complex treatment of the memory of the past, while others may perceive this as a terrifying and tasteless combination of beauty and horror, and in the case of Van der Heijden, even as an expression of a sort of necrophilia. Undoubtedly, these images bring to mind Susan Sontag’s notion of looking at such photos with mixed feelings of disgust and fascination. Actually, within the evolving discourse on the representation of the Holocaust, combining humor and Shoah and creating beauty out of the horrible is something we have seen before. In this case, we are not speaking about an artist whose purpose is to be provocative, but rather of the creativity of a mature, contemplative person for whom Jewish identity is of great significance.

Maarten van der Heijden, Tissues 1, 2010, lightbox with Duratrans-print

Furthermore, the work of Van der Heijden is significant in the context of Shoah art and the second generation. The artist explains his somewhat obsessive engagement with the Holocaust as an act of working through, or processing, trauma. According to him, the terrible images of the murdered victims of the Shoah are by and large hidden from the public eye. These are images that people would prefer not to see directly. “We tend to avoid these kinds of images,” explains the artist, “even in books that deal with the Shoah, mainly in Europe, it is rare to find these terrifying images.” Therefore, Van der Heijden intends to bring these images to the public consciousness. He not only speaks of doing this, but actually does it; in his own living room a triptych of three various colored works of this kind hangs on the wall. In one, a mixture of heads and limbs appears on a bright gold-yellow background. Another one contains a duplicated image of a man who committed suicide on the barbed wire fence of a concentration camp, presented against the background of psychedelic colors, blue, orange and rose. In the third, in the form of a duplicated mirror, legs protrude from a pile of corpses in a concentration camp, set against a background of shades of blue reminiscent of clear sky and water. The intertwined beauty and horror and the fact that the viewer is forced to gaze upon this ugliness bring to mind the critical words of New Leftist Guy Debord in his Society of the Spectacle (1967): “That which appears is good, and that which is good appears.” It seems as if Van der Heijden, in his work, wants to escape this vicious circle.

Maarten van der Heijden, Grotesques 3, 2010, C-print

Marianne Hirsch coined the term “postmemory” with regard to the second generation of the Holocaust. According to Hirsch, postmemory is a strong form of memory particularly because the connections of this memory to its source are not mediated by means of direct experience. Rather, they are created by filling in the empty spaces of memory by means of imagination and creativity. Postmemory characterizes the experience of those who grew up overwhelmed by the stream of events that took place before they were born, and of those who were shaped by traumatic events that are impossible to fully understand or reconstruct. The silence of Van der Heijden’s parents (regarding their Shoah experiences) left an empty space that the artist can only fill in third-hand, in this case, through horrific photos that document the victims. Here, postmemory creates within a place that is impossible to reveal, imagines in a place that cannot be remembered, and mourns a loss that cannot be repaired.

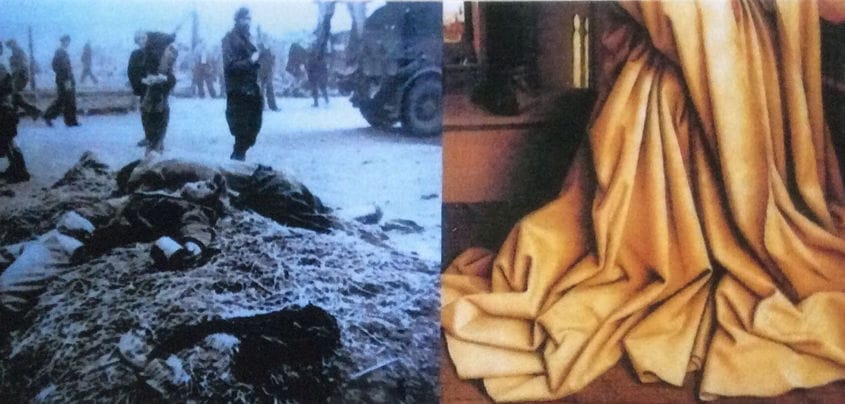

One of Van der Heijden’s works is created from a well-known image of a Jewish body in a concentration camp and is shaped into a scene of a classical crucifixion. Here there is a straightforward continuation of the theme of the “Jewish Jesus,” identified by art historian Ziva Amishai-Maisels. This was a common act of reappropriation by Jewish artists of images of Jesus as a crucified Jew. Marc Chagall, for example, protested against his contemporaries, as if to say, “You are again and again crucifying Jesus in your persecution of the Jews.” Another series, in maroon, red, orange, and brilliant blue, creates seemingly vaginal images through the repetition of images of bodies that were photographed in the camps. These works combine Eros and Thanatos. At first glance, they seem to be pleasant and moving, but a more discerning look reveals that they are appalling. The works of the artist, now on display at the exhibition at the Bezeq Building as part of the Third Jerusalem Biennale for Contemporary Jewish Art, juxtapose fragments of reproductions of classic baroque paintings with photographs of the Shoah (Stations of the Cross – Ecce Homo, 2017).

Maarten van der Heijden, Tissues 1 (detail), 2010, lightbox with Duratrans-print

Here the artist emphasizes hand gestures, the folds of garments, or images of torture, juxtaposing them with similar images from religious Renaissance art, displacing beauty with the very extremes of horror. Van der Heijden explains:

For me personally as a second generation Jew, when I saw these horrifying photographs of the Holocaust for the first time – I think I was twelve years old – it was a watershed in my life: it was as if there was something broken inside me forever. In this installation, I contrasted these horrific images with the – in my opinion – most beautiful images from art history: the Renaissance paintings of Van Eyk, Gruenewald, Cranach, and others. In the installation, there is the division between extreme horror and extreme beauty in the first place, but the Christian connotations of the Renaissance paintings are also relevant in relation to the Holocaust, a watershed in the history of the Jewish people.”

Maarten van der Heijden, Stations of the Cross – Ecce Homo, 2017, 14 C-prints

Indeed, atrocities have been represented throughout the history of art. The sufferings of Jesus or descriptions of heroic wars were common in the past, but expressions of horror from a critical perspective are primarily a modern phenomenon which began with Goya’s paintings Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War) from 1810 and 1820 and later continued in the field of photography. In contrast, in his works, Van der Heijden juxtaposes pre-modern classical images, in which the horror is basically concealed, with harsh, explicit photos from the concentration camps. The artist raises a crucial point by juxtaposing beauty with evil and horror. The main point of all his various works emphasizes that evil, cruelty, and wickedness were concealed by beauty in the past, as they are today. Despite the fact that images of war and horror are common today, when it comes to the Shoah, and in particular in the European context in which the artist works, the contemporary eye prefers to look away. In this reality, Van der Heijden is fiercely protesting: “You may not look away“ (Deuteronomy 22.3).

David Sperber, The Department of Gender Studies, Bar-Ilan University and the Shalom Hartman Institute, Jerusalemץ

David Sperber is an art historian, art critic and independent curator. In 2017, Sperber completed his Ph.D. dissertation, titled: “Jewish Feminist Art in the US and Israel, 1990-2017” – at the Gender Studies Program, Bar Ilan University, Israel (Supervisor: Professor Ruth Iskin, Department of the Arts, Ben-Gurion University). Sperber’s articles have appeared in numerous publications including academic periodicals, museum exhibition catalogs and in popular media. His most recent article, “The Liberation of G-d: Helène Aylon’s Jewish Feminist Art”, is forthcoming in Images: A Journal of Jewish Art & Visual Culture. In 2012 he co-curated the international groundbreaking exhibition “Matronita: Jewish Feminist Art” at the Mishkan Le’Omanut, Museum of Art, Ein Harod in Israel.

I like David Sperber’s observation on the issue

Of censorship I support all artists expressions

With out censorship and removal

From exhibitions . I was surprised to

Hear of it in a place such as Museum Hamachterot

That addresses historically a place of tourcher

In Israel during the British mandate. Seeing the actual work it did not arouse in me the anger I would associate

Which I was confronted as a child when I first saw the horrors the Nazis had done to nine million people

It maybe caused by the poor display

Space or un appropriate lighting of the work that did not come up to the examples mr.Sperber used to address the unfortunate action by the Museum director.

Bruria Finkel

| |