Helène Aylon (b. 1931) who was raised in an Orthodox home is one of the most prominent American artists in the feminist Jewish religious art movement that emerged in the 1990s. She can justifiably be called the Grande Dame of feminist Jewish art. Aylon’s art, like that of most American feminist artists in the 1970s and the 1980s, focused on the body and environmental art (eco-feminist art). During the 1970s and the 1980s these works were exhibited and collected by major museums in the United States. In the 1990’s Aylon began engaging in a radical feminist critique of the Jewish tradition. These works were displayed mainly in Jewish museums across the United States.

Aylon is perhaps best known for her installation “The Liberation of G-d” (1996) that was the first and central work in a series of installations named “The G-d Project: Nine Houses Without Women.” This twenty year project proposed a scathing feminist critique of Jewish texts and rituals. In “The Liberation of G-d” Aylon covered pages of the Bible with transparent parchment and highlighted with a marker the verses that she found offensive to a feminist reader, questioning verses that express sexist and misogynist views. She asks: “Do they belong in a holy book? Did God say it to Moses, or is it a patriarchal projection.” In this pioneering work the artist purged the text from its sexist and misogynic verses, as if to liberate God from the effects of patriarchy.

Aylon’s feminist critique precedents were in the first wave of the American feminist movement. Feminist leaders (who happened to be Christian) not only demanded social and legal changes but understood the power of the biblical tradition and Church status and thus worked for a radical change in consciousness. At the end of the nineteenth century, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the editorial board of The Woman’s Bible wrote a radical critique and reinterpretation of the seminal holy texts – the Old Testament and the New Testament. Aylon’s work also continues the radical manner that caricaturized the “second wave” of feminism in the 1970s, in line with Mary Daly’s ironic comment: “If we remove all identifying marks of patriarchy from the Bible, only a thin book will remain.”

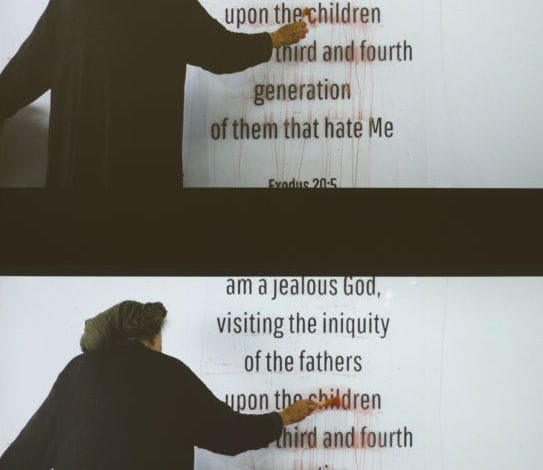

Helen Eylon, “Afterwords, For The Children: Wipe”

Another notable work of Aylon that was part of her “G-d Project” is titled “All Rise: The Beit Din as a ‘House’ of Three Women Judges” (2007-2009). It is the creation of a court room, representing a new “Beit Din” (Jewish religious court) headed by women even though the position of Judges within the Jewish Orthodox word is notoriously limited only to men.

“Afterword: For the Children,” is an appendage (and the finale) to Aylon’s twenty year “G-d Project.” Aylon dedicates her finale in this Project to the future generations, challenging the Ten Commandments which emanates in her view, from patriarchy – not from God. The second commandment of the Ten Commandments in the bible declares: “I am a jealous God and I transfer the sins of the fathers unto the children up to the third and fourth generation.” The text holds future generations responsible for the sins of their fathers. Aylon declares:

If I have sinned

That sin is my own

If my father has sinned

That sin is his own

If you have sinned

That sin is your own

It is not the sin of the newborn babe who smiles as the sun comes out

It is not the sin of the yet unborn, still crouching inside the womb

It is not the sin of the child on the bike

Or the child on the swing

Or the child on the school bus eager to go to school

Or the child waiting to graduate.

There is a holiday called Simchat Torah which translates, joy of the Torah.

Should I rejoice on this holiday?

Should I dance with the Torah as is the custom?

Or should I mourn?

In her seminal book “After Christianity” (1996), The feminist theologian Daphne Hampson’s pointed out that the male God represents what is considered perfection for men (power, singularity, self-villains, etc.), and therefore monotheistic religions are a “feminist nightmare.” However unlike Hampson and Daly, who called for women to leave the church and establish a Post-Christian religion, Aylon’s intention is to create change from within the Jewish religious world. Aylon expresses her criticism in the name of the religion and culture to which she herself belongs. She thus continues a practice that is prevalent among Jewish religious feminists, as well as among contemporary women artists dealing with institutional critique of the art world, who voice their criticism in the name of, as opposed to against, the institutions they criticize.

Helen Eylon,

“:Afterword, For The Children

The Air “Commandments

Whereas American Jewish feminist artists in the 1970’s and the 1980’s did not foreground their Jewishness but emphasize their gender identification in a collective movement, since the 1990’s, Aylon’s engagement with a critical stance related to her Jewish identity constitutes a ground-breaking, radical social avant-garde and sets itself a goal to effect changes in the Jewish religious world. Aylon’s art operates as socially engaged art that aims to reach beyond the walls of the Gallery and the museum, challenging the structures of religious patriarchy and also engaging in a dialogue with its representatives.

The article will also appear in the catalogue for the Jerusalem Biannle of Jewish Art, that will open October 2017. Helen Eylon’s “Afterword: for the children” (Curators: Dvora Liss and David Sperber) will be on show October 1st -November 16th.